Category Archives: English

Verbs in English and Portuguese. Or: Grammar vs. Morphology

| You can read this post in either Portuguese or English. Você pode ler este artigo tanto em Português quanto em Inglês. |

|

| English | Português |

Verbs in English and Portuguese. Or: Grammar vs. Morphology

I have been asked several times in the last weeks about a facebook post showing how much easier English is when compared to Portuguese. More specifically, verbs. The post in question compares the 5 different forms of an English verb, “do”, to 59 different forms assumed by the corresponding verb in Portuguese, “fazer”. The point being that Portuguese is more difficult because you need to learn more verb forms.

Like a great amount of what we see on the internet, this is not entirely correct. Indeed, when learning any given Portuguese verb you need to deal with tens of different individual forms, while, for English, you need to deal only with between 3 and 5 individual forms – “be” is an extreme case with eight forms. But, if you think that is enough to define how easy or difficult a language is, please, think again.

The problem here is that such a comparison is based on a wrong assumption. The same assumption behinds statements such as “Chinese has no grammar” (which was rather common a few years ago). It is the idea that “grammar” means simply “morphology”. Or, in other words, that idea that the grammar of a language consists only in the different inflections that a word may “suffer” to express changes of meaning or relations with other words.

Well, that is simply not true.

Morphology is just one part of grammar. Grammar are the rules that indicate how words can be connected to form sentences. Morphology deals only with the alterations you make to a word for that purpose. But inflection is not the only method used by a language’s grammar.

Take Mandarin, for example. (You can say “Chinese”, but that is not properly the name of the language.) Mandarin has almost no inflection. Which means, words in Mandarin don’t change their form to express different meanings or to connect to other words. For building sentences, Mandarin grammar relies on things like word order, composition, auxiliaries, particles, word choice &c. Just as an example: although Mandarin doesn’t have definite or indefinite articles such as “an” or “the”, and despite the fact that a noun cannot change its form, it is perfectly possible to indicate whether a noun is definite or indefinite in a Mandarin sentence.

- 有學生在學校受傷了。 – There is a student (indef.) hurt at the school.

- 學生來這裡了。 – The student (def.) came here.

(Please note: This is based on information obtained from friends who know Mandarin, as well as from online sources – see below. I’m no more than a noob in Mandarin.)

But let’s get back to the subject of interest here: the question of whether it is meaningful to compare this:

do - does - did - done - doing

to this:

faça - façais - façam - façamos - faças - faço - fará - farão - farás - farei - fareis - faremos - faria - fariam - faríamos - farias - faríeis - faz - faze - fazei - fazeis - fazem - fazemos - fazendo - fazer - fazerdes - fazerem - fazeres - fazermos - fazes - fazia - faziam - fazíamos - fazias - fazíeis - feita - feitas - feito - feitos - fez - fiz - fizemos - fizer - fizera - fizeram - fizéramos - fizeras - fizerdes - fizéreis - fizerem - fizeres - fizermos - fizesse - fizésseis - fizessem - fizéssemos - fizesses - fizeste - fizestes

Don’t you notice anything wrong here?

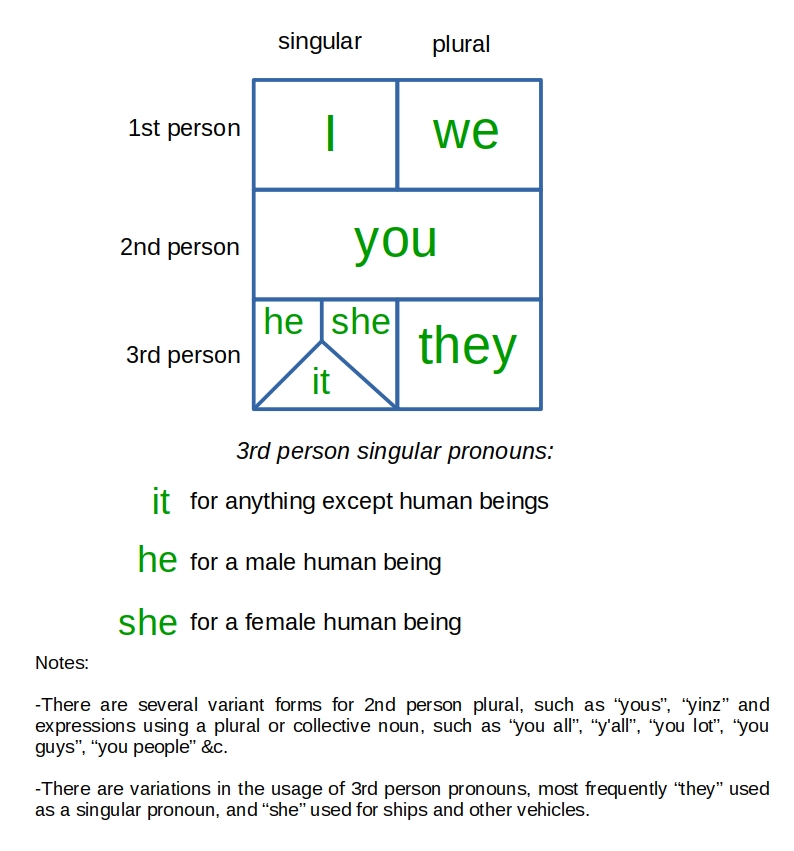

Yes, that’s what I mean: the 5 English forms simply don’t cover all the same ground as the 59 Portuguese forms. For doing the job of all the Portuguese individual forms, English needs things like modal and auxiliary verbs, personal pronouns – at least.

Even if we don’t take into consideration things such as context, collocations or idioms, i.e., considering only the basic meaning of each verb form, a real correspondence table would look more like this:

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| faça |

|

| façais |

|

| . . . | . . . |

| fazíamos |

|

| . . . | . . . |

| fizestes |

|

What gives the illusion that English is “easier” than Portuguese is the wrong assumption that morphology is all there is to a language’s grammar. Related to that is the matter of word boundaries. While in a Portuguese verb we condense notions of person, time and mood in one single word, in English you use separate words for each of these traits. So, there is no single word in English that can correspond to a verb form such as “faremos”; you need to put together a series of words, such as “we are going to do”. The difference is merely in the spelling; in speech, the English expression behaves basically as a single word – you need all the parts together, in that specific order, without anything between them, to convey the intended meaning. If you discount writing, you have /wɪəˌɡəʊɪŋtəˈduː/, which could as well be represented in writing as ‘wearegoingtodo’. Remember that spelling is just a convention. The future tense in Portuguese is a good example of such convention, as, in the past, the suffixes ‘-ei’, ‘-ás’ &c. were written as separate words ‘hei’, ‘hás’ &c.

My point is: while in one language you have to learn how to use bits of words (i.e., affixes), in the other language you have to learn how to use auxiliary words – and the rules in one case are as complex as the rules in the other. The workload is pretty much the same.

Reference:

- http://www.grammaticalfeatures.net/features/definiteness.html

- https://www.msu.edu/~changhs9/2004CLS40paper.pdf

- http://people.umass.edu/partee/docs/HornFestPartee.pdf

- http://www.grammaticalfeatures.net/features/definiteness.html

- https://www.academia.edu/16335882/Os_verbos_aver_e_teer_no_portugu%C3%AAs_arcaico_breve_sinopse

- http://www.filologia.org.br/anais/anais%20III%20CNLF%2052.html

Verbos em Inglês e Português. Ou: Gramática vs. Morfologia

Já me perguntaram diversas vezes nas últimas semanas a respeito de um post que roda no facebook, mostrando como o inglês é fácil em comparação com o Português. Mais especificamente, os verbos. O post em questão compara as 5 diferentes formas de um verbo em inglês, “do”, com 59 diferentes formas que o verbo correspondente em português, “fazer”, pode assumir. O argumento é que o português é mais difícil de aprender, uma vez que você precisa memorizar uma quantidade bem maior de formas verbais.

Assim como muito do que encontramos na internet, isto não está inteiramente correto. De fato, quando aprendemos qualquer verbo em português, precisamos lidar com dezenas de formas individuais diferentes, enquanto, no inglês, só enfrentamos de 3 a 5 formas individuais – sendo “be” um caso extremo com oito formas. Mas, se você acha que isto é suficiente para determinar o quanto uma língua é fácil ou difícil, então… por favor, pense novamente.

O problema aqui é que esta comparação se baseia em um pressuposto incorreto. O mesmo pressuposto que está por trás de afirmações como “o chinês não tem gramática” (que era bem comum alguns anos atrás). É a ideia de que “gramática” significa pura e simplesmente “morfologia”. Ou, em outras palavras, a ideia de que a gramática de uma língua consiste unicamente nas diferentes flexões que uma palavra pode “sofrer” para expressar mudanças de significado ou relações com outras palavras.

Bem, isto simplesmente não é verdade.

A morfologia é somente uma parte da gramática. Gramática é o conjunto de regras que indicam como as palavras podem se juntar para formar orações. A morfologia trata apenas das alterações que você pode ou deve aplicar a uma palavra para tal finalidade. Mas as flexões não são o único método utilizado pela gramática de uma língua.

Tomemos o mandarim, por exemplo. (Você pode dizer “chinês”, mas este não é propriamente o nome do idioma.) Basicamente, o mandarim não tem flexões. Ou seja, as palavras em mandarim não sofrem alterações em sua forma para expressar diferentes significados ou para se relacionar com outras palavras. Para criar orações, a gramática do mandarim utiliza coisas como ordem das palavras, composição, auxiliares, partículas, escolha de palavras &c. Apenas como um exemplo: mesmo que o mandarim não tenha artigos definidos ou indefinidos, ou seja, os equivalentes a “um, uma” ou “o, a”, e apesar do fato de que um substantivo não pode mudar sua forma básica, é perfeitamente possível indicar se um substantivo é definido ou indefinido:

- 有學生在學校受傷了。 – Há um estudante (indef.) ferido na escola.

- 學生來這裡了。 – O estudante (def.) veio aqui.

(Lembre-se, por favor: isto se baseia em informações obtidas com amigos que conhecem o mandarim, bem como em fontes encontradas na web – ver abaixo. Eu não sou nada além de um noob em mandarim.)

Mas voltemos ao assunto de interesse aqui: se faz realmente sentido comparar isto:

do - does - did - done - doing

a isto:

faça - façais - façam - façamos - faças - faço - fará - farão - farás - farei - fareis - faremos - faria - fariam - faríamos - farias - faríeis - faz - faze - fazei - fazeis - fazem - fazemos - fazendo - fazer - fazerdes - fazerem - fazeres - fazermos - fazes - fazia - faziam - fazíamos - fazias - fazíeis - feita - feitas - feito - feitos - fez - fiz - fizemos - fizer - fizera - fizeram - fizéramos - fizeras - fizerdes - fizéreis - fizerem - fizeres - fizermos - fizesse - fizésseis - fizessem - fizéssemos - fizesses - fizeste - fizestes

Você não está notando nada errado aí?

Sim, é isto o que eu quero dizer: as 5 formas do verbo inglês simplesmente não abrangem a mesma gama de significados que as 59 formas do verbo português. Para realizar o trabalho de todas as formas do verbo português, o inglês precisa de coisas como verbos modais e auxiliares, e pronomes pessoais – no mínimo.

Mesmo se não levarmos em consideração fatores como contexto, locuções e expressões idiomáticas, ou seja, mesmo que consideremos apenas o sentido básico de cada forma verbal, uma correspondência mais realista ficaria mais ou menos assim:

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| faça |

|

| façais |

|

| . . . | . . . |

| fazíamos |

|

| . . . | . . . |

| fizestes |

|

O que dá a ilusão de que o inglês é “mais fácil” que o português é o pressuposto incorreto de que a morfologia é tudo o que há para aprender na gramática de uma língua. Relacionado a isso está o fator do limite entre as palavras. Enquanto um verbo portugês condensa as noções de pessoa, tempo e modo em uma só palavra, em inglês temos que usar palavras separadas para cada um destes elementos. Assim, não há uma única palavra em inglês que possa corresponder, sozinha, a uma forma verbal como p. ex. “faremos”; você precisa juntar uma série de palavras, tais como “we are going to do”. A diferença está unicamente na grafia; na fala, a expressão inglesa se comporta basicamente como uma palavra só – você precisa de todas as partes, juntas, nesta ordem específica, sem nada entre elas, para produzir o sentido desejado. Se você não levar em conta a grafia, nós temos /wɪəˌɡəʊɪŋtəˈduː/, que poderia muito bem ser representado na escrita por algo como ‘wearegoingtodo’. Lembre-se de que a grafia de uma língua não passa de uma convenção. O futuro do indicativo em português é um bom exemplo de tal convenção, já que, no passado, os sufixos ‘-ei’, ‘-ás’ &c. eram escritos como palavras separadas ‘hei’, ‘hás’ &c.

O que eu quero dizer é: enquanto uma língua te obriga a aprender a usar pedaços de palavras (ou seja, afixos), em outra língua você é obrigado a aprender a usar palavras auxiliares – e as regras em um caso são tão complexas quanto as regras no outro. A carga de trabalho que você tem de realizar é, em termos gerais, a mesma.

Referência

- http://www.grammaticalfeatures.net/features/definiteness.html

- https://www.msu.edu/~changhs9/2004CLS40paper.pdf

- http://people.umass.edu/partee/docs/HornFestPartee.pdf

- http://www.grammaticalfeatures.net/features/definiteness.html

- https://www.academia.edu/16335882/Os_verbos_aver_e_teer_no_portugu%C3%AAs_arcaico_breve_sinopse

- http://www.filologia.org.br/anais/anais%20III%20CNLF%2052.html

Online classes

I had some online classes today with native speakers. That’s the way to go for learning languages. When I’m studying Русский by myself it feels like I’m rocking. Then I have a class with a native speaker and… I find out I just suck at it. 🙂 Best way to see what, where and when you have to improve.

The classes included 日本語, Русский and తెలుగు, using English, Français & Português as intermediate languages.

moth – English – Word of the Day – 2015-11-04

Moths comprise a group of insects related to butterflies, belonging to the order Lepidoptera. Most lepidopterans are moths and there are thought to be approximately 160,000 species of moth, many of which are yet to be described. Most species of moth are nocturnal, but there are also crepuscular and diurnal species.

dead – English – Word of the Day – 2015-11-02

English recording

Text Reading (American version)

Text Reading (British version)

The longest and most boring day of the year.

English – 2015-01-04

- tryst /trɪst/ – a prearranged meeting or assignation, now especially between lovers to meet at a specific place and time; a mutual agreement, a covenant; to arrange or appoint (a meeting time etc.).